TL;DR

Agentic coding has crossed a threshold. With tools like Claude Code, Cursor, and Codex, engineering throughput is moving from “a few PRs a day” to “dozens”. Opus 4.5, in particular, hits different in day-to-day use.

Velocity is increasing faster than confidence. Shipping gets cheap. Knowing what to ship, what to keep on, and what to roll back becomes the hard part.

This is an experimentation problem, not a coding problem. When change volume explodes, teams need systems that govern exposure, preserve causal correctness, and keep decision-making trustworthy.

Spotify argues for separating personalization and experimentation stacks. Their rationale is solid. My bet is that many teams will still be forced to converge the workflows (even if the infrastructure stays separate).

Table of Contents

Editor’s Note

The Agentic Shift in Software Delivery

What practitioners are actually seeing

“When AI writes almost all code”: the new abstraction layer

The velocity-confidence gap (why this becomes an experimentation problem)

Why this matters to the business (not just engineering)

Diffusion of innovation (and why this is not evenly distributed)

Spotify: Personalization and Experimentation should be separate stacks (and why I think workflows will still converge)

Spotify’s position (the core points)

Where I agree

Where my view differs: convergence is coming (for many use cases)

Closing: Let’s compare notes

🌟 Editor's Note

Pictured: Marcel Toben, ~2016. New Year’s resolution still: finally update my profile photo.

Welcome to the second edition of the Experimentation Club Newsletter. And yes, I am late: it is not Sunday anymore.

A weekly cadence was… ambitious. Between the day job and a few side quests, I learned quickly that “weekly long reads” require either (a) a team, (b) a much calmer life, or (c) fewer hobbies. For now, I will keep publishing when I have something that feels worth your time.

In parallel, we are planning the next Berlin Experimentation Meetup for February. If you would like to share an experimentation topic on stage at this or one of the next events, please reach out. We will announce the date and speakers soon.

I am also still developing the format. The letter should not just be a list of curated links after all. I want it to be more deliberately topic-driven: fewer items, deeper synthesis, and clearer implications for experimentation practice.

Over December and into January, I spent a lot of time doing what many developers do when left unsupervised: falling down rabbit holes. Agentic coding was the big one. Claude Code, Cursor, Codex, and a steady stream of new workflows (and new hype) are changing how software gets built.

And in the last weeks since November, I have felt a real shift first-hand: not “AI helps me write code faster,” but “the shape of software development is changing.” The links below are the best articulation I have seen so far of what’s happening and why it matters.

The Agentic Shift in Software Delivery

A few things came together around late November and December. Anthropic released Opus 4.5, and a lot of seasoned engineers started reporting the same thing: this one hits different.

What’s different is not a benchmark number. It is the lived experience of agents doing real work end-to-end: reading code, running commands, iterating on errors, and moving through multi-step tasks with less supervision.

A. What practitioners are actually seeing

Burke Holland: “AI coding agents can absolutely replace developers” (provocative, but instructive).

Burke’s post is one of the clearest “field reports” from someone who actually tried to build things, not just speculate. He describes Opus 4.5 as the first agent experience that consistently gets most things right on the first try, and then uses the CLI feedback loop to fix itself when it doesn’t.

The important detail is not the bold claim. It is the mechanism:

The agent builds, runs, reads errors, and iterates.

It handles “glue work” (auth, backend, storage) that traditionally breaks agent flows.

The workflow is lightweight: voice dictation, a strong agent harness, and minimal ceremony.

Eric J. Ma: from “coding” to “directing”.

Eric’s framing is the mental model shift many people are bumping into: you stop thinking in syntax and start thinking in outcomes. He explicitly calls out that his review loop changed as well: he pays more attention to the model’s reasoning and intent, and less to line-by-line scrutiny in the moment.

Two takeaways matter for engineering leaders:

The bottleneck moves from implementation to validation. If you cannot validate quickly, you cannot benefit from the speed.

Legacy assumptions become drag. He describes needing to “unlearn” old limitations as models improve.

Gergely Orosz + Boris Cherny: how Claude Code is built, and what “AI-first engineering” looks like.

Gergely’s deep dive is valuable because it connects product, architecture, and operating model. A few points worth pulling out:

Claude Code spread internally after getting filesystem access; it became a tool “people got hooked on.”

The tech stack was chosen to work well with model behavior (TypeScript/React/Ink/Yoga/Bun), and the team reports that a large share of the code is written by the tool itself.

The system runs locally (no VM sandbox), which increases capability but makes permissions and safety design central. The permissions model and layered settings (user/project/company) are described as the hardest part.

They prototype aggressively: an example describes ~20 prototypes of a single UX feature in a couple of days, iterating by prompt, testing, and feedback.

On org-level productivity: the piece reports PR throughput increasing even while team size doubled, attributing this to Claude Code adoption.

This is the key pattern: AI increases the number of “attempts” per unit time. And attempts are what drive product evolution.

Enraged Camel: the “this would have taken us 4–6 months” story.

This post is a useful counterweight to pure hype because it is about a risky, tedious, real migration: re-architecting multi-tenancy and refactoring across server + database, in a two-person startup.

Their claimed results:

Completed in ~2.5 weeks rather than 4–6 months.

The human still reviewed everything and made the major decisions (“not vibe coding”).

They used “discuss → plan doc → implement” to reduce agent drift and manage long tasks.

They explicitly built security regression tests for cross-tenant leakage, and treated “context pollution” as a real operational hazard (fresh chats as a reset).

Even if you discount the exact multiplier, the underlying signal is clear: some categories of foundational engineering work are collapsing in cost when you combine strong models with agentic loops.

B. “When AI writes almost all code”: the new abstraction layer

Gergely’s follow-up post captures the second-order effect: once AI writes most of the code, the job becomes managing a new abstraction layer (agents, subagents, prompts, tools, permissions, workflows) and continuously recalibrating expectations.

He also shares a quote from Boris Cherny describing a month where he did not open an IDE and Opus 4.5 produced ~200 PRs.

Whether your number is 20 PRs or 200 PRs is not the point. The point is what happens when:

shipping becomes dramatically cheaper, and

iteration becomes dramatically faster, and

the number of changes outpaces human attention

This creates what I think is the core dynamic for 2026:

C. The velocity-confidence gap (why this becomes an experimentation problem)

When engineering throughput explodes, execution velocity increases faster than decision confidence.

You can ship more things than you can responsibly evaluate.

That tension shows up as practical failures:

Too many variants, not enough statistical power (or analysis capacity).

Too many overlapping changes, not enough causal clarity.

Too many “small safe tweaks,” not enough alignment on what you are optimizing for.

Too many rollouts, not enough rollback discipline.

In other words: the bottleneck shifts from coding to governance and measurement.

What this shift means for experimentation (my take)

If you run experimentation platforms, analytics, or growth engineering, you should assume this changes your world in three ways:

1) Experimentation moves from “project” to “operating system”.

In high-velocity environments, experimentation cannot be a special event with a long setup and a long analysis tail. It needs to be the default control plane for change:

consistent assignment

exposure tracking you can trust

layered rollout + holdout patterns

fast reversal

decision logs (what changed, why, and what happened)

2) You will need to scale confidence, not just scale shipping.

Organizations will have to invest in “confidence infrastructure,” not in more dashboards:

metric definitions that are stable and reviewable

guardrails that prevent obvious harm without human intervention

automated sanity checks (SRM, logging, event coverage, invariant violations)

fast feedback loops that reduce time-to-learn

3) The definition of “experiment quality” changes.

In an agentic world, the failure mode is not “we ran too few experiments.”

It is “we ran too many low-integrity changes.”

Experimentation maturity becomes less about “how many tests did you launch” and more about:

decision integrity under high change volume

preventing interference

making outcomes auditable

protecting users while still learning fast

A practical way to think about it: three rates that must stay balanced

To keep an organization stable, these three “rates” need to match:

Change rate: how many user-facing changes you can ship

Safety rate: how quickly you can detect and contain harm

Learning rate: how quickly you can produce reliable evidence

Agentic coding increases change rate. If safety rate and learning rate do not keep up, you get chaos dressed up as productivity.

D. Why this matters to the business (not just engineering)

Those three rates are not an internal platform concern. They determine whether “moving faster” turns into commercial advantage or commercial risk.

If change rate outpaces safety rate: speed turns into operational and brand risk. Incidents become more frequent or harder to contain, customer trust erodes, and teams spend more time stabilising production than improving the product. Reliability starts competing with growth.

If change rate outpaces learning rate: speed turns into wasted roadmap. You ship more, but you do not make decisions faster. The organisation accumulates changes with unknown impact, teams debate metrics after the fact, and “wins” become harder to trust. Over time, this degrades confidence in experimentation and in data-driven decision-making.

If safety rate outpaces change rate: caution turns into opportunity cost. Heavy governance can keep systems stable, but it can also slow iteration enough that teams stop exploring meaningful product bets and default to incremental, low-risk changes.

The risk is not any single rate. The risk is imbalance. As the cost of change drops, the bottleneck shifts to organisational confidence: detecting harm fast and producing evidence you can act on.

E. Diffusion of innovation (and why this is not evenly distributed)

This shift will not hit every company the same way. Diffusion theory is a useful lens: innovators and early adopters will operationalize agentic workflows first, then the early majority follows when patterns and tooling stabilize.

But my bet is that this change is not avoidable for digital product companies. The economic pressure is too strong:

competitors ship faster

internal teams expect faster iteration

“why does this take two weeks?” becomes an uncomfortable question

The leadership question is not “if,” it is how to adopt without destroying reliability.

If you lead teams, a pragmatic stance for 2026 is:

adopt agents first where validation is cheap and rollback is easy

invest early in measurement and guardrails (before velocity spikes)

treat experimentation and rollout governance as first-class engineering problems, not process problems

3) Spotify: Personalization and Experimentation should be separate stacks (and why I think workflows will still converge)

Spotify’s post “Why We Use Separate Tech Stacks for Personalization and Experimentation” is well argued and worth reading. Kudos to the authors Yu Zhao and Mårten Schultzberg.

Spotify’s position (the core points)

They acknowledge the overlap.

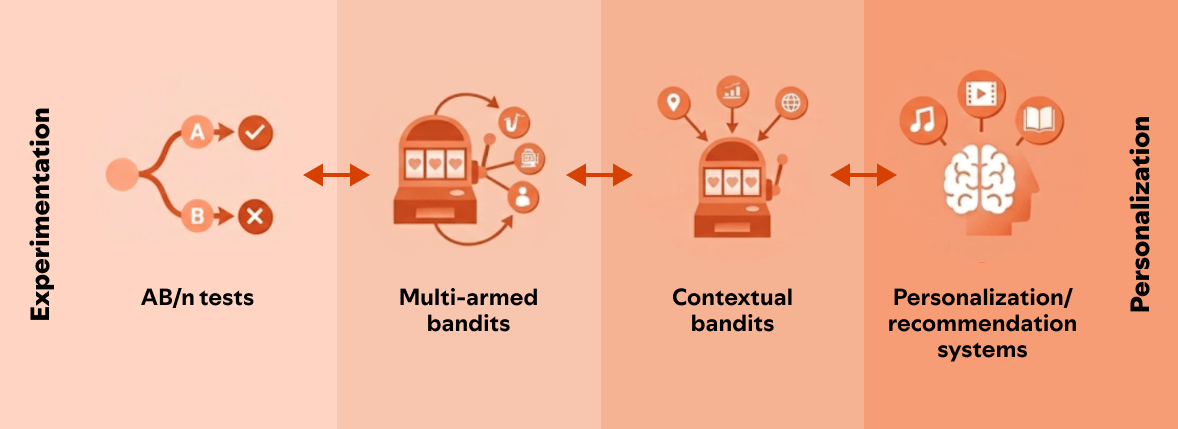

They describe the progression from A/B tests → multi-armed bandits → contextual bandits, and explicitly state that contextual bandits start to look like personalization.

Figure 1: The progression from A/B testing to personalized recommendation systems through multi-armed and contextual bandits. (Image by the authors)

They keep infrastructure separate for practical reasons:

Personalization needs ML infrastructure: training, serving, low-latency features, model variety, and production constraints.

Experimentation needs to evaluate everything at scale, across many product teams, with low friction and standardized measurement.

Mixing bandits and experiments in the same tool can create confusing dependencies (because you may need to A/B test the bandit system itself).

They are skeptical on bandits for experimentation in practice.

Their key critique is that typical multi-armed bandits optimize for a single objective, while real businesses need multi-metric trade-offs and guardrails. They argue that multi-objective bandits increase complexity so much that usability and adoption suffer, and that straightforward A/B testing across hundreds of teams delivers more real value.

Where I agree

Spotify’s argument is strong on two dimensions that most teams underestimate:

Infrastructure realities matter. “Just put personalization into the experimentation platform” is naive once latency, feature stores, model serving, and operational constraints show up.

Complexity kills adoption. If only a small elite can use a method, it does not scale as an organizational capability.

Where my view differs: convergence is coming (for many use cases)

I think the infrastructure split can remain valid, while workflows converge.

The reason is simple: we are entering a world of feature abundance.

more variants

more iteration

more dynamic configuration

more local optimization problems inside products

In that world, “personalization” and “experimentation” stop being separate categories and start being two modes of the same underlying loop:

decide what to show a user (a policy)

serve it safely

measure the effect

update the policy (manually or automatically)

Spotify calls out real challenges (multi-objective trade-offs, long-term metrics). I largely agree those are hard.

But I see them less as reasons to keep the worlds apart, and more as the problems we have to solve if we want to operate at higher velocity without harming users or the business.

A concrete prediction for 2026:

many companies will still keep ML and experimentation infrastructure separated

but they will push toward a unified “decision layer” where rollouts, experiments, and adaptive policies share common governance, measurement, and auditability

In practice, this means:

experiments become easier to spin up (because change volume demands it)

rollouts become more measured (because risk accumulates faster)

optimization loops get more constrained (because safety has to be faster than optimization)

That is the shift I am watching most closely.

Closing: Let’s compare notes

If any of this resonates, I would genuinely like to hear where you agree, where you disagree, and what you are seeing in your own org. Are agentic workflows already changing your delivery velocity? And if so, what did it break first: code review, observability, release management, experimentation, or alignment?

You can reach me via LinkedIn or email. I read everything and I am always interested in new perspectives, especially the “this is what actually happened in production” kind.

One more thing: we are preparing the next iteration of the Berlin Experimentation Meetup for February. If you would like to share an experimentation topic on stage at this or one of the next events, please reach out. We will announce the date and speakers soon.

2026 is going to be wild.